These days, calling someone amateur is an insult. If you’re an amateur, you don’t have the “skillz to pay the billz.” By amateur, we generally mean an inept know-nothing with no expertise—a hack.

But I want to rescue the label amateur from its current dishonor. It’s my opinion that the greatest potential in the arts today comes from amateurs. We need more of the amateur spirit, not less. What do I mean?

What it Means to be an Amateur

It’s worth noting that, technically speaking, the only thing that separates a professional from an amateur is getting paid. Professionals make a living from their craft. Amateurs do not. It’s strange I know, but the only defining difference between a professional and an amateur is that an amateur does it for free.

So when and why did the term amateur begin to mean unskilled? When? Around the time that our culture started to believe that money was the measure of all value. Why? Because if you can’t or won’t make a living from something, it must be because you aren’t very good at it.

We should not value art on the basis of its marketability, so it would follow that we should not value artists on how much money they can make from their art.

But as I’ve written before, art is not a commodity. We should not value art on the basis of its marketability, so it would follow that we should not value artists on how much money they can make from their art.

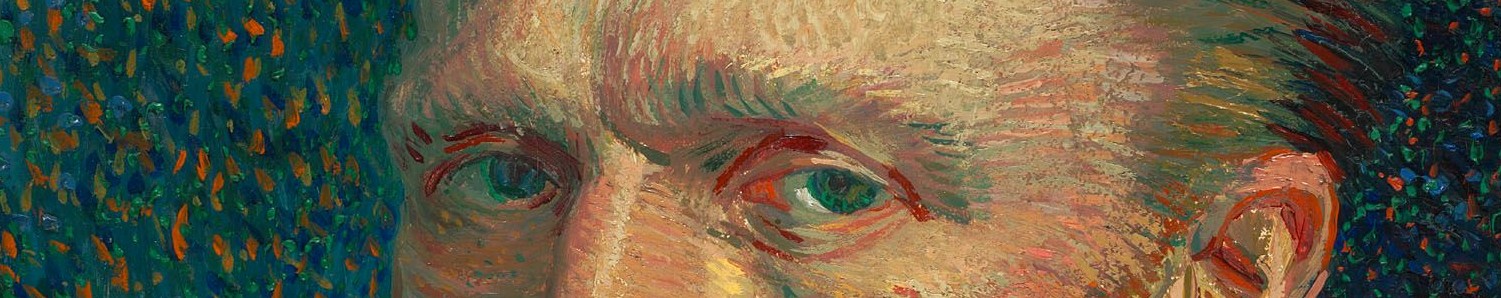

Many artists that are currently considered great never made money from their craft. Vincent van Gogh is an obvious example: “Van Gogh only sold one painting during his lifetime: Red Vineyard at Arles. . . . The rest of Van Gogh’s more than 900 paintings were not sold or made famous until after his death.”

So, technically speaking, Van Gogh was an amateur painter. And if Van Gogh had been working in the church today, it is almost certain that his leaders and peers would have told him to quit his “hobby” and get a real job. Or, at least, they would have encouraged Van Gogh to change his painting style to make it more marketable: “Look at Jean Béraud. He’s making a living from painting. And he’s quite famous. Why not paint more like he does?”

So why did Van Gogh keep painting? Because he loved it and couldn’t do anything else. Van Gogh may have been criticized in his time for stubbornly pursuing his own unique style in spite of popular opinion, but looking back from our vantage point, we can all be thankful he didn’t quit.

Yet, for all that we know about artists who were unappreciated in their own time, we continue to put a similar pressure of marketability on artists today. I can’t tell you how many times artists have told me about this pressure. Sean Sullivan, of Warbler, told me he once got this advice from a well-meaning member of his church: “So you think God is calling you to be a musician? I’ll tell you what you need to do. Look at the musicians who are making a living from music, and then imitate what they’re doing.” Such advice is quite common. It seems so reasonable, and the pressure to follow it is great. I mean, who wouldn’t want to make money doing what they love?

But think about what this “professionalism” has done to the arts. The professional spirit has actually become quite mercenary, and this has sapped the arts of its vitality and freshness. You have an alarming number of “Christian” artists who aren’t even Christians—they’re just riding the Jesus gravy train. And then, on the other hand, you have an equally alarming number of authentic Christians who are pressured into making “marketable” art instead of making the far more bracing, convicting, refreshing, and unique art that God has actually called them to make.

And Yet …

There are a few things here that I am not saying: First, I am not saying all professional artists are mercenaries. There are obviously professional artists who make art with integrity in spite of the pressure to change their approach for acclaim or money. But these professionals actually possess the amateur spirit. That’s what I meant by the title of this article. All the best artists would still do what they do for the love of it even if they weren’t getting paid.

Second, I am not saying all art that is unpopular is therefore good and worth supporting. Some art is obviously unsupported in its time because it isn’t good, and that art is generally forgotten forever.

Third, I am not recommending that the artist completely ignore his target audience. The artist’s job is to give the audience what they need, even if sometimes it isn’t what the audience wants. In order to do this, the artist must consider his target audience deeply and carefully—sometimes knowing them better than they know themselves.

Conclusion

It’s hard to know how to encourage and support the amateur spirit. But one question I ask all artists is this: “Would you make your art the way you make it if money were no concern?” Most artists who have “made it” in our day (both within the church and without her) cannot answer “Yes” to that question. And that should trouble us, especially considering that the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil (1 Tim. 6:10). What kind of evil have we done to the arts (and to artists) by forcing artists to make marketability their primary aesthetic concern?

What kind of evils have we done to the arts (and to artists) by forcing artists to make marketability their primary aesthetic concern?

Everyone suffers in this scenario. The church is missing out on groundbreaking art by forcing our artists to have already become successful in the market before we will support them. Because of this, many artist Christians with truly prophetic voices are ignored, discouraged, and destitute. Most of them keep producing ignored art (thanks be to God), but they also have to work tent-making jobs to care for themselves and their families. This reduces their artistic productivity.

These are the local artists that the local church should be considering and supporting—the ones who don’t quit over the course of years in the face of great discouragement. These are the torch-bearers of the amateur spirit. We need more of them.