I imagine Pilate asked Jesus, “What is Truth?” with the same tone of hopeless resignation that many people ask, “What is Art?” It seems like, as with discussions of truth, we all know more or less what’s standing right in front of us even when we aren’t willing or able to articulate it clearly.

Nonetheless, whenever there are disagreements about art, you can be sure at least one peanut in the gallery will torpedo the discussion with “unanswerable” questions. Usually, these questions and definitions serve to close discussion rather than open it. I have no intention of doing that here.

I want Christians to learn better how to submit to one another in the fear of Christ. Art provides such a wonderful arena in which to do this. What a person delights in provides a profound window into what he worships—no matter what he might profess on Sunday. For this reason, having some agreeable terms with which to discuss art can help us know each other—to know what we really love, and how we love it.

Other People’s Definitions of “Art”

So, to begin, how have others defined art? Any given discussion or attempted definition of art usually includes at least one of three distinct focuses: on the artist, on the art work itself, or on the audience. One could focus on the artist—on his or her intentions, personal history, training (or lack thereof), or even on the artist’s responsibility to a community. One could focus on the artwork—on its craft, its medium, its message, its relationship to genre(s), or on its marketability. Lastly, one could focus on the audience—its needs, its desires, its enjoyment, or its interpretations.

Where “definers” choose to focus will greatly affect how they define art. Artist-oriented definitions of art usually focus on the intention, emotions, or unique expression of the artist.1 Art-oriented definitions will focus on the craft, beauty, or truth inherent in the art object itself. 2 Audience-oriented definitions will focus on the transforming attention or emotional response of an audience. 3

Importantly, all three focuses can produce fruitful discussions of art. Yet none of these three focuses hold the exhaustive truth.

A Working Definition of Art

The simplest definition of art is this: “Art is whatever you call art.” Though this might seem unhelpful at first, this definition relocates the discussion to other, generally more useful, questions. “Is this piece of art good or bad?” or “Why are you calling this art?” Some people dismiss Jackson Pollock or John Cage with “Well, that’s not even art!” They could just as easily (and more helpfully) say, “Well, I don’t think that’s any good.” Or “What was the purpose in making this and calling it art?”

In order to have these discussions, however, we must first understand what makes art art. So let’s discuss three interconnected attributes that, when put together, distinguish art from other forms of communication. Art is:

- Crafted/Selected

- Representational/Representative

- Normative/Standardizing

Art is Not Just Beauty and Emotion

You will notice that there are two elements missing from my list which you might have grown accustomed to seeing in discussions of art—beauty and emotions. I don’t think art has to come from or evoke emotions to qualify as art, though certainly it can and often does involve the emotions. Furthermore, quite a few of the most famous and timeless pieces of art would not be called “beautiful” in the commonly understood sense of “pleasurable to the senses.”

The discussion-closing peanuts in the gallery discussed above like to appeal to both emotions and beauty (defined according to their own spirits and tastes, of course) to exclude certain works without further discussion. Aiming at inclusion with distinction, I have tried to organize our three interconnected elements to include everything someone might call art while giving enough distinction to “art” to separate it from “everything else.”

Art is Crafted/Selected—Attention

Things become art when an artist transforms them by a designation of and for attention through craft or selection. Just as a person staring into a fixed point in the sky will inevitably attract imitators from those who pass by, an artist first models the attention he desires to see in an audience.

Artistic attention will manifest itself in various degrees of craft. All artworks exist on a spectrum from highly wrought on one hand to merely selected on the other. But Michelangelo’s highly wrought “David” and Marcel Duchamp’s merely selected “Fountain” both qualify as art because in each case a “found” material has been selected out of or transformed from its original configuration into a new, special arrangement which invites (and perhaps even demands) the audience’s special focus.

Oftentimes, critics of found object, abstract, or folk art say that the lesser craftsmanship common to these genres makes them less worthy of attention. I agree that artists should not expect an audience to grant their pieces more attention or thoughtfulness than they themselves have granted it. But, on the other hand, an artist invests much of the time and effort in a good “found object” piece before any manipulation of materials begins. In other words, the idea of a piece, which might involve hours and hours of thought and experience, deserves as much attention as the craft of a piece which might involve as many hours of training or manual labor or little time at all.

Either way, you can distinguish a piece of art from the reality that surrounds it by the simple fact that someone selected it out of or re-arranged it from its natural arrangement or context in an attempt to warrant an audience’s special attention. By designating something for attention, the artist will then imbue an object with significance—in the literal sense of the word. By selecting it out of reality, an artist turns a thing into a sign.

Art is Representational/Representative—Sign-ificance

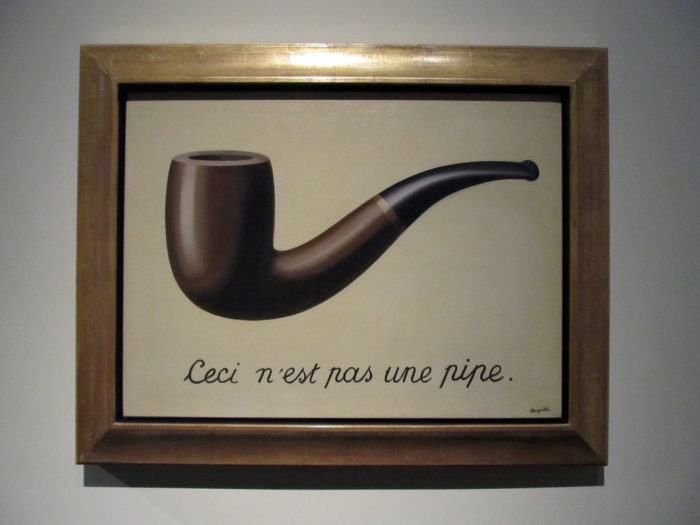

Art involves sign language. Or, more properly, art communicates through signs. A painting of a pipe is not a pipe itself, it re-presents or points to a pipe. A fictional parable does not have to be factual to be true—it points to a truth beyond itself. Art, even art in words, points to something beyond itself as the true object of its attention.

Without this crucial second element, one could properly call any communication art. Most do not call purely propositional communication art because propositions do not represent anything or point to anything beyond themselves. Propositions constitute in themselves the communicated message. Signs point to a message beyond or behind the sign.

The sign-ificance of an artwork will range in a spectrum from pure allegory to pure concretion. Whereas allegory generally makes it clear that each element of an artwork points to things, truths, or relationships in the real world, purely concreted work (which ironically includes both abstract and “hyper-realistic” iterations) both aim at coming as close as possible to being things in the real world.

For instance, an abstract painting makes no attempt to “deceive” you into thinking it is anything other than material paint on a material canvas. Similarly, “reality” drama might attempt to convince that “real life” unfolds before you on the screen. I would still allow both hyper-realism and abstraction in the category of “art,” however, because they select from within reality, and they both ultimately point to something other than themselves. The selection/attention creates significance—the artist says something or points to something beyond the intrinsic reality of the art object itself, even if this significance holds a fairly minimal difference from the thing itself.4

This leads to our third element, for the significance of an artwork based on its designation/transformation out of reality generally points to some norm or standard in the mind of the artist. If the artist is good, he will be able through his artwork to convince an audience of how he sees the world. What began as representation can become representative.

Art is Normative/Standardizing—Intention

No matter what an artist may say about their artistic intentions (or lack thereof), all art says something about the artist’s worldview. For an artwork to achieve success, the audience should have the experience the artist intended, and that experience will always serve to draw the audience closer to the artist’s vision of the way things are or the way they should be.

Even an untouched photograph, as a selection from within reality and a representation of what was seen, will serve an artist’s vision of the norm. And even the same photograph can “say” something different in one collection or context than it does in another. What distinguishes photo-journalism from art photography is the degree to which the photographer attempts “objectivity.” But as we all know, much photo-journalism is more art than science, simply because it selects representatively to establish an often implicit norm.

For instance, National Geographic recently back-pedaled on its interpretation5 of a viral video of a starving polar bear traversing an ice-free landscape. They had added the caption, “This is what climate change looks like.” Several people raised the valid point that the bear’s condition could have been caused by factors other than climate change. Captioned in this way, the video became fiction: as manipulative as a picture of a blizzard with the caption “Climate Change Clearly a Myth.”

This is both the power and the danger of art, and why we must recognize the presence of art, especially when a communicator claims “artlessness.” On one hand, art can package humongous truths in tiny packages in ways that even a child can understand. On the other hand, through selective signification, art can present falsehoods or manipulations in a convincing way. Knowing that no art is without some normative intention will help greatly to avoid missing the lie (or missing the truth!) that the artist assumes into his work.

Conclusion

With these three elements of art—craft, representation, and standard, we have at least three ways to ask questions about art. For instance: “What kind of attention does this art ask for? Does the artist use good craft or does the piece’s selection or re-arrangement exhibit insight or promote discovery and realization? Why? Did the artist pay even more attention to his piece than his piece seems to require of me? What is the original context (reality) from which or out of which this work was crafted/selected, and what does its new context or arrangement communicate?” Or we might ask, “How does this art incorporate signs or constitute a sign? Is this art allegorical or figurative? Of what? What does it point to?” And lastly, “Why did the artist make this? What is the artist attempting to (or accidentally succeeding in) communicating? What norm or standard does the art seem to promote? Does the artist do a good job of establishing his view of the world? What worldview does the artist actually hold? Are there more than one options for interpreting this piece?”

To close, our working definition of art based on our three elements is this: “Art is representational communication crafted or selected to promote an artist’s normative vision of or for reality.”

So, with this, please sally forth and let us know how these elements help you have productive discussion about the arts. And please let us know your thoughts and experiences in the comments! Do you think we’re missing anything here?

*******************

Also, check out the discussion we had over this question on the Renew the Arts podcast: S2E1: What is Art?

- For instance, Oscar Wilde said, “Art is the most intense mode of individualism that the world has known.” ↩

- For instance, Leonardo DaVinci said, “Art is the Queen of all sciences communicating knowledge to all the generations of the world.” ↩

- For instance, Leo Tolstoy (never known for his succinctness) posited his own definition of art after dismissing so many others: “Art is not, as the metaphysicians say, the manifestation of some mysterious idea of beauty or God; it is not, as the aesthetical physiologists say, a game in which man lets off his excess of stored-up energy; it is not the expression of man’s emotions by external signs; it is not the production of pleasing objects; and, above all, it is not pleasure; but it is a means of union among men, joining them together in the same feelings, and indispensable for the life and progress toward well-being of individuals and of humanity.” ↩

- Note here that only God’s art is total art, and therefore it is reality. ↩

- For National Graphic subscribers, see the original article here. ↩

Where definitions for art are going to get really interesting and informative is when AI becomes more prevalent in the creation of art.

Joe

That is a fascinating question related to this, for sure. Have you read this article? https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/is-art-created-by-ai-really-art/

I haven’t read that article, but most such articles are high on my reading list at the moment. I’ve written about this, as well,

https://natureofthebeat.svbtle.com/ai-commits-suicide-at-27-years-old-news-at-11

A good article is on Medium:

https://medium.com/@thementalupdate/art-and-beauty-in-the-age-of-machine-intelligence-7e743867a9d6

where it discusses a difficult perspective to answer, “based on Ada Lovelace’s idea that a machine should not be considered intelligent in the same way as a human, until a machine can originate an idea it was not designed to do.”

I’ve been troubled by how all the talent based reality TV shows keep talking about how art is supposed to evoke an emotional response, that this is what defines (good) art. In reality this is just a different Modern Utilitarian definition, a tool for emotional manipulation.

AI has a leg up on “creating” art as a product, whose only purpose is to analyze prior work and find the common denominators of the most popular and remix those into something else. If that is all art is, then yes, we will be supplanted by AI.

But can an AI create something relevant? As another article on Medium puts it, “Alongside history, art has had different meanings and interpretations, ” (https://medium.com/@orge/will-the-next-picasso-be-a-robot-9438482b4208)

Is there art without freewill, without sacrifice, without context? Currently an AI can only produce what it was designed to produce. But when we talk about art being part of human nature, an intrinsic part of our being, are we not saying the same thing about us? Is the difference simply that we can chose not to create art?

But then, an AI doesn’t exist without being created by a human, even if all these other criteria are met, does it truly create outside the human spirit?

So many existential questions that we don’t have the answer to.

Oh, and the potential for forgery! Oy!

Also on Medium by me:

https://medium.com/@jfutral/for-the-humanity-in-art-efc21af4d950

Joe

Art definition

https://www.arteallimite.com/en/2019/06/20/de-que-hablamos-cuando-hablamos-de-los-sabios-incompetentes-iv/

Precisions about definition of art

https://www.arteallimite.com/en/2019/08/12/contra-los-farsantes/