Your hosts Allison and Michael discuss some reasons to appreciate Modern Art, bringing up some of the most famous of the nearly 70 movements comprised by it. With all of its snark, modern art has a lot to say about honesty in the face of the brutal realities of human existence, and Christians can learn something from it about how to make “ugly” art the right way.

Stay tuned at the end for a classical guitar piece by Brazilian composer Villa-Lobos, performed again by Phil Hodges.

“Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2”

Marcel Duchamp

1912

“Fountain”

Marcel Duchamp

1917

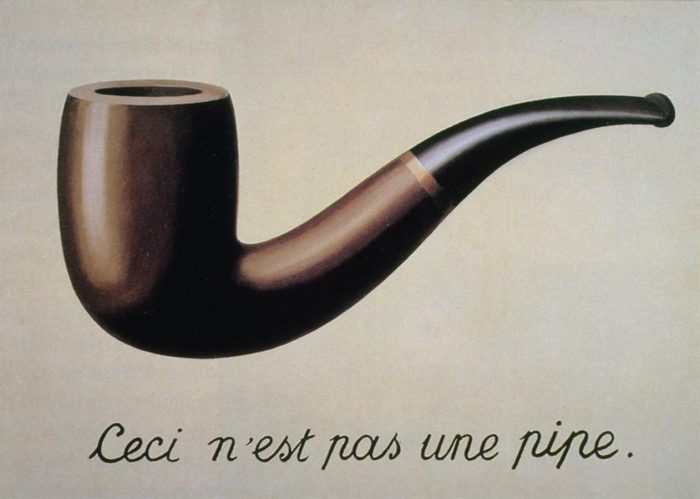

“The Treachery of Images”

René Magritte

1929

I didn’t even know you guys started up your new season until this podcast. So right now I am playing catch up.

One of the things I find myself often battling, among audience and artists alike, is this notion that there is some ideal art, usually classical, but just as often Modern but from a different perspective. To reduce it a bit further, Michael actually touched on it a bit when complaining about Rothko and Pollock being essentially repetitive. But this is not anything new to painters. How many times did van Gogh paint the view from his window in his room at the asylum? How many times did he paint the same cypress tree? How many times did Cezanne paint a still life, searching for the “apple-ness of an apple”.

Of course, I am not saying you have to like Rothko or Pollock (even as they are two of my favorites), but I do see their work as artist looking to plum the depths of their inspiration. Additionally if you look at the progression of their work you do see that they are moving in a direction. Early Rothko color-fields are less defined as later. In his final works he moved from the color fields floating in a background color to filling the canvas edge to edge. Maybe that is too subtle a distinction, but it is significant none-the-less.

With those two in particular, even as we dub them “abstract-expressionists”, Rothko insisted his work is not an abstract of anything. Neither is it representational. It is exactly what he painted.

Pollock insisted nothing he painted was an accident, every drip or drop was intentional and deliberate.

But mostly I most often confront this idea that everything pre-modern (and by that the Modern detractors are usually meaning anything post-war) gets kind of clumped together in this hazy, rose colored glasses view. They do not or do not want to believe anything was disruptive. Each movement was simply a natural progression, a universally agreed upon next step of art.

That just isn’t the case. The impressionists (not even the post-impressionists yet) were initially roundly criticized for their hazy or fuzzy depictions and bold use of color. It is reported that at one of Manet’s showings a man wanted to bash a painting with his walking cane.

“Gothic” was a originally a derisive descriptor of that style of architecture.

Bottecelli’s _Birth of Venus_ was disruptive as a female divine figure that wasn’t Mary.

Even though I largely disagree with Francis Schaeffer’s and hans Rookmaaker’s characterization of Modern art being lost in despair, their mostly reductionist analysis does rightly point out the influence of science.

The Renaissance also marked science’s drive to learn about things as they really are. And I think contemporary art and thought are as struck by the uncertainty of science as anything. All of a sudden science is telling us things aren’t as they seem. Reality isn’t what we think it is or what we think we see. I think few things have contributed as much to our uncertainty today than science. Why wouldn’t we reflect that in our art?

Only in hindsight can we assume that it was all a simple, smooth progression. The disruptions seem less disruptive through the lens of time.

Never mind the idea that “my cat could do that”. Oy.

Looking forward to catching up and hearing more,

Joe

I am enjoying and appreciate the series already. I hope Allison does not mistake my commentary as criticism of what both of you have thoughtfully presented thus far. I agree that art history is important for much of what I have heard you articulate so far.

Joe