This is a guest post by Quenton Frank Brooks, an adjunct literature professor currently living in Israel. He was gracious enough to allow the Foundation to publish his thoughts on Death is Their Shepherd. Since not much has been written on the narrative portion of the project, we’re pleased to present this report in honor of Death is Their Shepherd’s one-year anniversary coming up this Halloween/Reformation Day.

And just in case this sort of thing matters to you, consider this your spoiler alert.

*****************

Every week, I meet my sister at the library for coffee and books. We talk, read, and watch videos. I know that at some point, she will intentionally use incorrect English. It comes with the territory: I am an adjunct English professor, and she is trying to bother me. I’m used to it. Unlike her, some other people are afraid to talk to me, lest I judge their poor English. None of this gets under my skin, but I appreciate a third response: people ask if I have read works by their favorite writers. If I haven’t, I am provided with a list of books or poems that I am told I must read. Sometimes, I research these recommendations, but most of the time, no one mentions them to me again, and we mutually forget about it.

While at church one Sunday, a friend approached me with Michael Minkoff’s short story, Death is Their Shepherd, and an album by the same name. Plenty of friends have told me about their favorite literary pieces, but no one had ever given it to me on the spot. The cover was interesting. It featured a cloaked Death herding sheep with a shepherd’s staff. The title at the top of the page had the band name “Physick” beneath it. It looked like death metal to me, which is not usually the type of music I listen to. I agreed to tell him what I thought and began reading.

As I opened Death is Their Shepherd, I saw it was divided into five chapters called “suites,” each of which paralleled a suite on the accompanying CDs. On the back, readers are told to “Listen, read, listen,” and “repeat as necessary or desired,” meaning participants should listen to the album, then read the book from beginning to end, and then listen to the CDs again for further insights.

The apothecarial suggestions on the back of the narrative companion. Merely suggestions. Interact as you will.

One person or a small group could benefit from listening to this music and reading the book, and just in case readers cannot understand the lyrics to the songs, they are printed in the front of the narrative companion.

The actual story is about Zak, a teenager troubled by a train accident that paralyzed his sister and killed his father. Abandoning his Christian faith, he befriends Lucien, a college student who helps Zak sneak into bars. After spending a night at a bar, Zak finds his home’s front door locked, leading him to spend the rest of the night on his back porch. He is then visited by Death, a human-like creature in black, and the rest of the short story describes Zak’s surreal and often grotesque visions exploring death in the light of eternity, thus altering the teenager’s view on his life and the afterlife.

These visions are important because they deal with life’s most difficult questions, particularly those of death and what comes after. Nobody can offer perfect answers to these questions. “Why does God allow death?” “How could a loving God send people to Hell?” “Why do good people suffer?” An adjunct professor in a library loaded with books certainly cannot answer these questions sufficiently. Yet, we must seek answers nonetheless. This goes without mentioning the other topics addressed by Minkoff, such as family tragedy and the nature of suffering.

While Minkoff does not always offer definitive answers, he handles the content responsibly and expresses a variety of views. Zak’s grief after his father’s death feels real and honest, including Zak’s early declaration that either his “dad’s death is meaningless. Or God is cruel” (51). Many readers, religious and non-religious alike, have had similar thoughts. Everyone will find something that he or she relates to.

This broad appeal comes from the personality of the author as seen on Physick’s Facebook page, where the band is labeled “electric Puritans.” This odd juxtaposition displays another balance between multiple points of view—traditional yet contemporary. Readers are able to trust the author because he has invested serious thought into his ideas by understanding several points of view, not just his own.

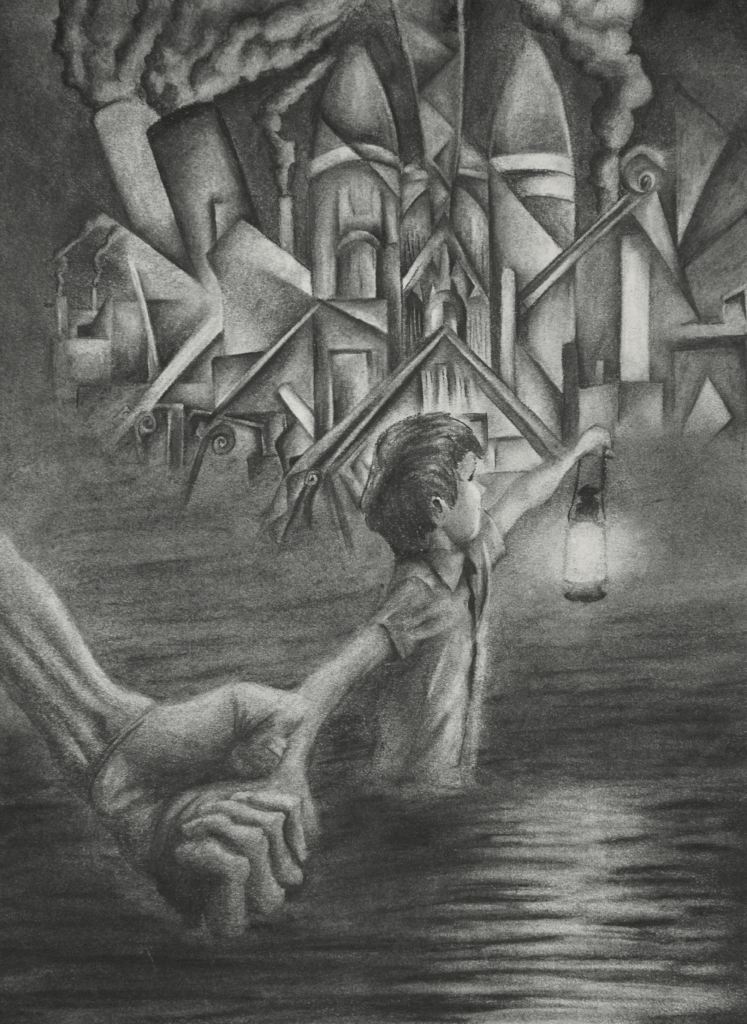

In addition to the ideas, the imagery used to represent the ideas is brilliant. In the first chapter alone, Minkoff offers a vivid description of one of his most compelling images, “The Black Factory,” which produces garbage for billions of people who are “black and glistening like hot tar and squeezed so close together that they looked like one roiling body of black sludge” (28). These people fight and kick each other for the garbage coming from the factory, an image of humanity and its ever-increasing desire for vain, material possessions.

“The Black Factory,” by Derrick Otis and Rusty Hein

After reading the first chapter, I placed the first CD into the player. The CDs comprise a narrative concept album – an experimental album that follows a storyline. There are two CDs: the first CD is black and decorated with a crown of thorns, an image of suffering and death, and the second is white with a crown of holly, representing life and resurrection. The first CD, the black one with the crown of thorns, has edgier, experimental music, featuring Gregorian-like chants, dialogue from the book, and operatic voices. This music reflects Zak’s early, dark spiritual condition. The white CD with the crown of holly has lighter and more hopeful music, reflecting Zak’s progressing spirituality.

The CDs for the album portion of “Death is Their Shepherd”

Although the album and book tell the same story and convey similar ideas, they do not match exactly. They were not meant to, as stated by Minkoff, “we did not correlate them perfectly and exhaustively. We tried to serve the album as music, the narrative as literature, and the illustrations as visual art” (1). At times, I suspect the music came before the short story; at others, I think the narrative. Because the CDs and book work independently, both are enjoyable on their own but are amplified by each other. I knew I would have to describe the songs and short story to my sister when we sat down for coffee.

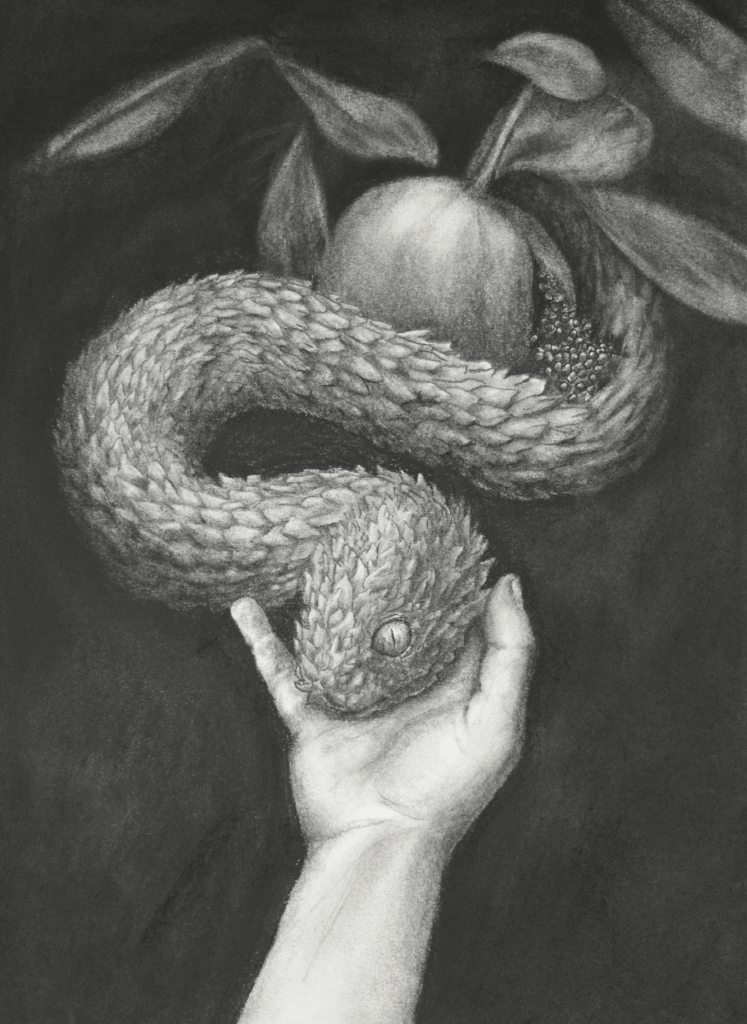

I read more. The music and imagery is at its best in “Suite 2: The Skull,” in which Minkoff recreates the biblical account of the fall in the Garden of Eden.

“The Woman and the Serpent,” by Derrick Otis and Rusty Hein

This chapter brings readers to the heart and thrust of the short story—redemption. While readers are probably familiar with Adam and Eve’s encounter with the serpent, this chapter is filled with enough new images that it is initially unrecognizable. Instead of focusing on traditional characters or setting, Zak watches a battle of light and darkness as they interact among the man, woman, and serpent, all of whom serve to destroy the light around them and die, only to be filled with a dull, diminished light. It ends with Eve watching the generations after her, hoping for a redeemer, but instead finding children similar to herself and her husband.

Her despair is amplified in the eighth song, “We’ve Been Misled,” in which a choir describes humanity, which “lives to die,” just like the original parents. She becomes a melancholy character as the song conveys the seriousness of death, which feels entirely evil as nature “cries out” against its existence. Listening to this song, listeners can easily see why a redeemer, Christ, is so important.

In addition to Eve, Minkoff crafts a complicated Adam. Because people inherit traits and learn habits from their parents, every trait can be traced to the original parent, Adam. Zak notes that Adam’s “voice sounded familiar. It reminded me of every voice I’d ever heard. Listening to him was like talking to myself” (37). Humanity inherited even death from its forefather. With this understanding, Adam is the ultimate “everyman” mirror, a stand-in for all readers. This removes any emotional distance between the readers and the mythic, almost otherworldly Adam. He becomes relatable.

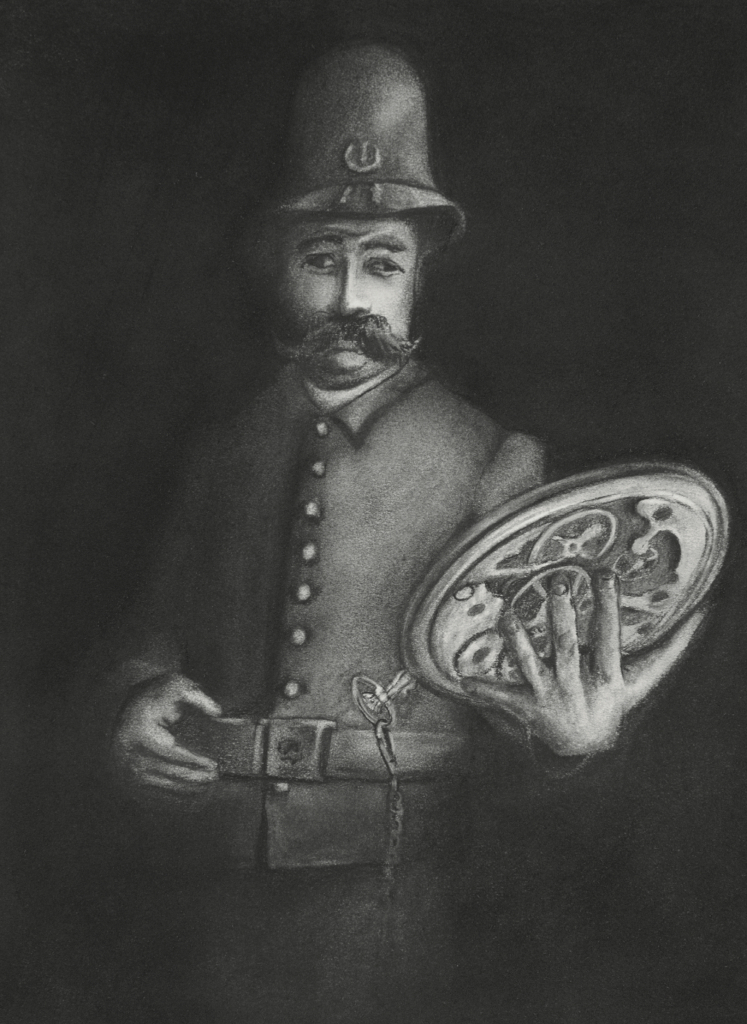

After “Suite 2: The Fall,” Zak’s visions move onto other characters as vivid as Adam and Eve that provide unique perspectives about death. The most alien character is the Clock Keeper, who seems like a character straight from Pilgrim’s Progress and is too nonchalant about Zak’s upcoming damnation.

“The Cockeyed Clock Keeper,” by Derrick Otis and Rusty Hein

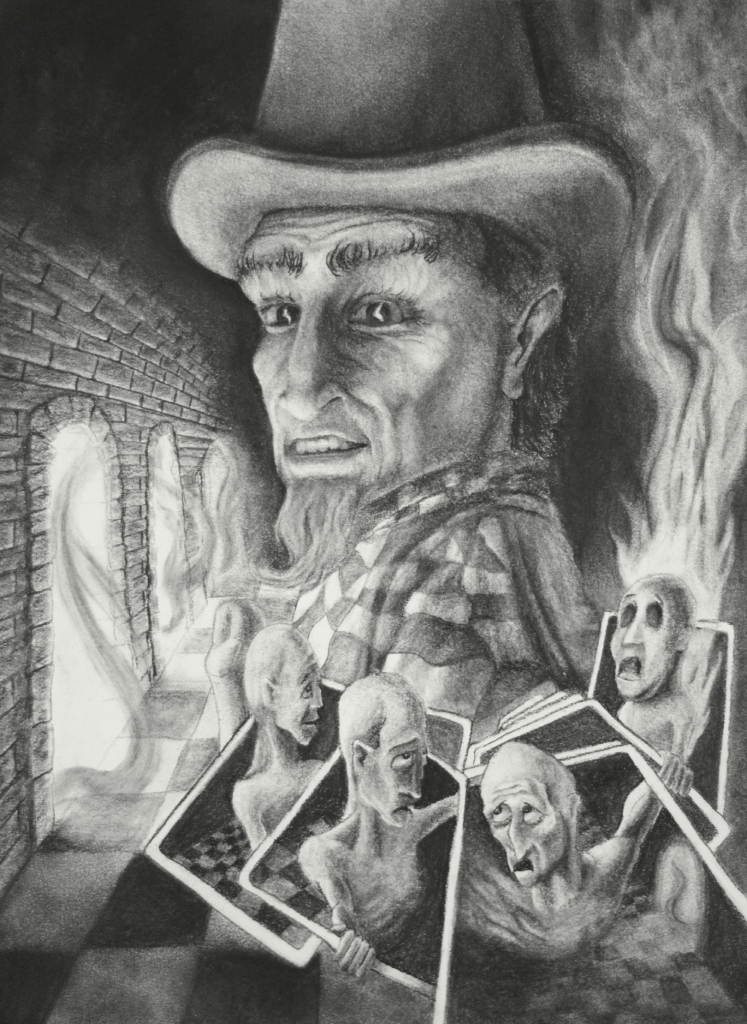

After this brush with Hell, Zak meets the devil, Woland, named after another famous demon in Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel, The Master and Margarita. Interestingly, both interpretations of Woland are portrayed as professors, perhaps revealing they specialize in a unique field of knowledge, seducing human souls into eternal damnation. Readers might see a jab at religious academia in general, perhaps suggesting a connection between Woland and Screwtape, a demonic professor in The Screwtape Letters.

“The Trickster,” by Derrick Otis and Rusty Hein

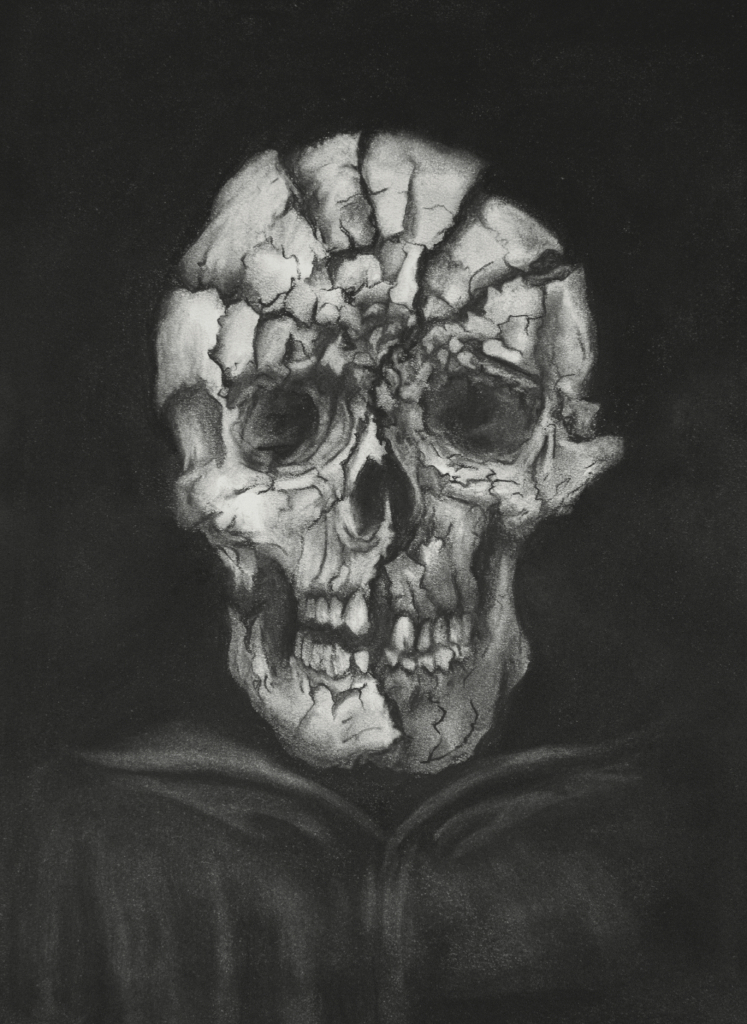

Contrasting Woland, the Upright Man –the tale’s Christ figure– is also present. He plays a continuous card game with Woland, only to bet everything on a single game and lose, resulting in the Upright Man’s humiliation and death in the Black Factory. As a result of this card game, Zak finally talks to Death, an ancient, shattered skeleton dreading destruction as a result of the Upright Man’s death.

“Death Lifts His Cloak,” by Derrick Otis and Rusty Hein

Although these characters offer an absorbing look into spiritual matters, readers might initially feel the first eight pages are not that engrossing. They do not feature grotesque imagery but instead focus on Zak’s interaction with his friend, Lucien, at The Deck. This blatant disconnect is heightened by the chapters’ perspectives: the first eight pages are in third person and the following chapters are in first person.

Yet, these first pages should not be ignored. They anchor the narrative and characters in reality before moving onto the more obscure, surreal world of the visions. They also establish themes and images developed later in the text, especially toward the work’s end.

This is particularly true of the character Lucien, whose name is a reference to “Lucifer,” Satan’s name as a cherub before he sinned. Structurally, this similarity in name highlights parallels between Lucien and Woland, Minkoff’s devil. While at The Deck, Lucien mentions it has a “lotta hotties” (18), which is later echoed by Woland when he says, “Lotta hotties here tonight, eh?” (64). Furthermore, the title “The Deck,” refers to Woland’s deck of seven billion cards, representing his hold on the souls of humanity. Lastly, Zak dances with Lucien, just as he and Death later dance with Woland, showing Zak has “danced with the devil” since the beginning of the short story. Thus, Zak’s arc gains more depth: he begins the work following the devil, only to stop by the night’s end.

These connections between the first pages and the visions highlight another strength of the short story—the ambiguous nature of Zak’s dreams. In the early pages, Zak becomes intoxicated at the bar, and readers never learn if the following sights are real or a result of the narrator’s intoxicated mind, recently disturbed by his father’s death. Because the visions parallel Lucien and the night at The Deck, Zak’s brain might be recycling scenes from earlier in the day: the bar is having its effect on him. A similar understanding suggests that the alcohol opens Zak’s mind to another reality, a dimension only available through intoxication. On the other hand, perhaps the drinks played no role and the visions are real, an understanding supported by the complexity of his thoughts and the change of his perspective on death. We’ll never know. No answers are provided, leaving their nature up to the interpretations of the readers, who will have plenty to think about when they are finished reading.

Having read and reread the short story, I shared my favorite passages with my sister over coffee. I was particularly impressed with the Clock Keeper, who downplays Zak’s death, saying “Nothing civil ever got so without death” (48). This line was one of my favorites. Even as my sister and I sat comfortably in a clean, polite coffee shop, death’s role in our lives and in developing our environment through the ages was an undeniable reality.

As if to prove this significance, after I finished reading to my sister, a man I never met before approached my table. Identifying himself from the outset as an atheist, he asked me for the name of the short story I was holding. “It sounds really interesting,” he said. I told him about the work and explained that I had reread it several times (including the first eight pages) and highly recommend it. I told him I particularly like the obscure nature of the story and how various chapters are largely open to interpretation, while the few core ideas are hard to misinterpret. He said he would find a copy.

We all relate to death, regardless of our religious views. Everyone dies, and and we all need to understand death before we do. This means that projects such as Death is Their Shepherd will always hold significance. I wish more people would hand me works like this.

*****************

If you want to experience Death is Their Shepherd, you can download a digital copy.

Or, if you want to hold something tangible in your hands, you can order the double-CD album and perfect-bound narrative companion from Bandcamp.